In November 2016, as

India-Pakistan tensions escalated in the weeks after the attack in Uri and

India’s much publicised strike-back, workers at the Kishanganga Hydel

Electricity Project in Gurez in North Kashmir

experienced for the the first time the dangers of the Line of Control. In all,

18 shells fell from across the LoC, just a kilometre

away over the hills, on both sides of the dam, which was then close to

completion.

“All of us just left whatever we

were doing and ran into the tunnel,” said Sanjay Kumar, an employee of the

construction company building the dam.

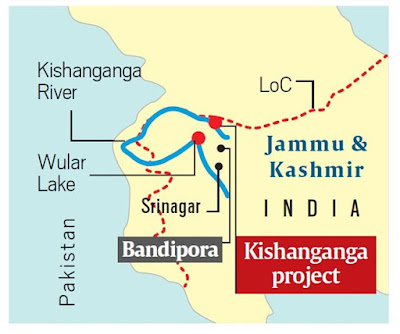

The tunnel, completed in June

2014, is an integral part of the KHEP — it takes the water from the Kishanganga

River in Gurez Valley to an underground power station

at Bandipora in the Kashmir Valley. Back then, there was no water in it.

According to dam officials, along with the workers, a large number of villagers

too, rushed into the tunnel for shelter, and demanded to be evacuated.

“We had to call the Army for

help,” a dam official said.

“But that was the first and last

time this happened in all my years here,” said Kumar, who joined the project in

November 2009.

On Monday, following intelligence

reports of cross-LoC infiltration bids in Gurez, the government decided to review security at KHEP. Hundreds of CISF personnel currently guard the dam. An Army camp deployed on the LoC is nearby, providing an

added layer of overall defence for the dam. During a recent visit by this

correspondent, a row of artillery guns inside

the camp was visible from the road, their barrels

trained at the mountain.

If India decided to locate the

project there despite the evident dangers of the LoC, it could not have been

without the confidence that it could handle this challenge, dam officials who

did not wish to be named, told The Indian Express.

The biggest defence, said the

officials, is that any act to destroy the dam

would actually pose the greatest danger to Pakistan

— the maximum impact would be felt downstream, across the LoC, in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. As the Kishanganga flows,

the LoC is only about 10 km from the dam, and habitation begins almost

immediately. The first village in PoK, along the banks of the Neelum, as the

river is known across the LoC, is Tawbal.

Of the 27 villages in Gurez, only

six are located downstream along the banks of the Kishanganga, and all have

been shifted uphill due to the dam.

However, even assuming that the

dam is targeted, shelling from across the LoC does not pose a real danger,

officials said. The dam is located in a gorge, and is

not in the direct line of fire. In the event that a shell does hit it,

the dam, one official said, “is a heavy structure, and

can withstand shelling”.

A more serious concern is sabotage by an individual or groups, said the

official. But that too would pose the same dangers of flooding downstream. The

river is wide enough to cause flooding at a discharge of about 2,000 cumec

(cubic metres per second). The Kishanganga dam has a pondage of about 7 million

cubic metres, but how this will translate into water flow will depend on the

extent of damage to the dam, and consequently, the time it would take for it to

flow out.

The people

who live in the villages near the dam site are also thought of as another layer of security. In Kashmir, the people of Gurez are considered pro-India. Many are

directly or indirectly employed by the Army.

As for the other parts of the

project, the tunnel is bored deep in the mountains, and transports the water of

the Kishanganga to an underground power station in Bandipora in the Kashmir

Valley. Officials say that these portions of the dam are inaccessible, and

would be difficult if not outright impossible to target.

Credit: Indian Express Explained

(http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/kishanganga-hydel-electricity-dam-security-india-pakistan-army-pakistan-shelling-5187314/)

Reach Us

if you face difficulty in understanding the above article.

No comments:

Post a Comment